Action-angle coordinates¶

galpy can calculate actions and angles for a large variety of

potentials (any time-independent potential in principle). These are

implemented in a separate module galpy.actionAngle. This module contains

classes for computing both the forward (x, v) –> (J, O, a)

and the reverse (J, a) –> (x, v, O) transformations. It is

also possible to compute most forward transformations as methods of the

Orbit class, which is typically the simplest way to compute actions,

frequencies, and angles for a given orbit.

Tip

If you want to quickly and easily compute actions, angles, or frequencies using the Staeckel approximation, using the Orbit interface as described in this section is recommended. Especially if you are starting from observed coordinates, as Orbit instances can easily be initialized using these.

Forward action-angle transformations can be calculated for the following potentials/approximations:

Isochrone potential

Harmonic potential

Spherical potentials

Axisymmetric potentials with the adiabatic approximation

Axisymmetric potentials with the Staeckel approximation

Static potentials with a general orbit-integration-based technique

One-dimensional potentials

There are classes corresponding to these different potentials/approximations and actions, frequencies, and angles can typically be calculated using these three methods:

__call__: returns the actionsactionsFreqs: returns the actions and the frequenciesactionsFreqsAngles: returns the actions, frequencies, and angles

These are not all implemented for each of the cases above yet. The adiabatic and Staeckel approximation have also been implemented in C and using grid-based interpolation, for extremely fast action-angle calculations (see below). Forward transformations are discussed in this section.

Reverse action-angle transformations can be calculated for the following potentials/approximations:

Isochrone potential

Harmonic potential

1D potentials

Axisymmetric potentials using the TorusMapper.

Reverse transformations are discussed in this section.

We start by discussing the forward and reverse transformations for the two specific potentials: the isochrone and the harmonic potentals.

UPDATED IN v1.8.2 Action-angle coordinates for the isochrone/harmonic potentials¶

The harmonic and isochrone potentials are the only potentials for which all of the actions, frequencies, and angles can be calculated analytically and for which the action-angle transformation can be straightforwardly reversed. For the isochrone potential, we can do this in galpy by doing

>>> from galpy.potential import IsochronePotential

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleIsochrone

>>> ip= IsochronePotential(b=1.,normalize=1.)

>>> aAI= actionAngleIsochrone(ip=ip)

aAI is now an instance that can be used to calculate action-angle

variables for the specific isochrone potential ip. Calling this

instance returns \((J_R,L_Z,J_Z)\)

>>> aAI(1.,0.1,1.1,0.1,0.) #inputs R,vR,vT,z,vz

# (array([ 0.00713759]), array([ 1.1]), array([ 0.00553155]))

or for a more eccentric orbit

>>> aAI(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1)

# (array([ 0.13769498]), array([ 1.3]), array([ 0.02574507]))

Note that we can also specify phi, but this is not necessary

>>> aAI(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.13769498]), array([ 1.3]), array([ 0.02574507]))

We can likewise calculate the frequencies as well

>>> aAI.actionsFreqs(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.13769498]),

# array([ 1.3]),

# array([ 0.02574507]),

# array([ 1.29136096]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.79093738]))

The output is \((J_R,L_Z,J_Z,\Omega_R,\Omega_\phi,\Omega_Z)\). For any spherical potential, \(\Omega_\phi = \mathrm{sgn}(L_Z)\Omega_Z\), such that the last two frequencies are the same.

We obtain the angles as well by calling

>>> aAI.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.13769498]),

# array([ 1.3]),

# array([ 0.02574507]),

# array([ 1.29136096]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.57101518]),

# array([ 5.96238847]),

# array([ 1.24999949]))

The output here is \((J_R,L_Z,J_Z,\Omega_R,\Omega_\phi,\Omega_Z,\theta_R,\theta_\phi,\theta_Z)\).

To check that these are good action-angle variables, we can calculate them along an orbit

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> o= Orbit([1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.])

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,100.,1001)

>>> o.integrate(ts,ip)

>>> jfa= aAI.actionsFreqsAngles(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts),o.phi(ts))

which works because we can provide arrays for the R etc. inputs.

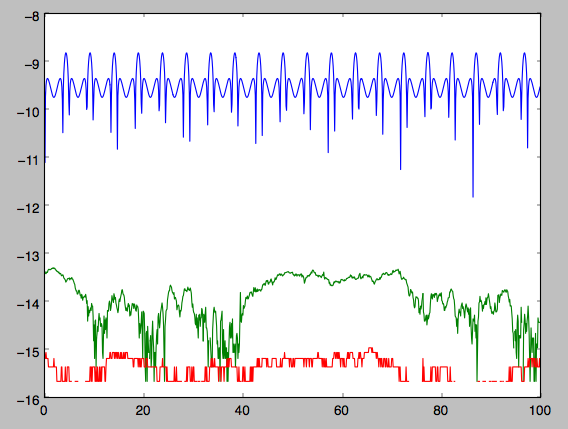

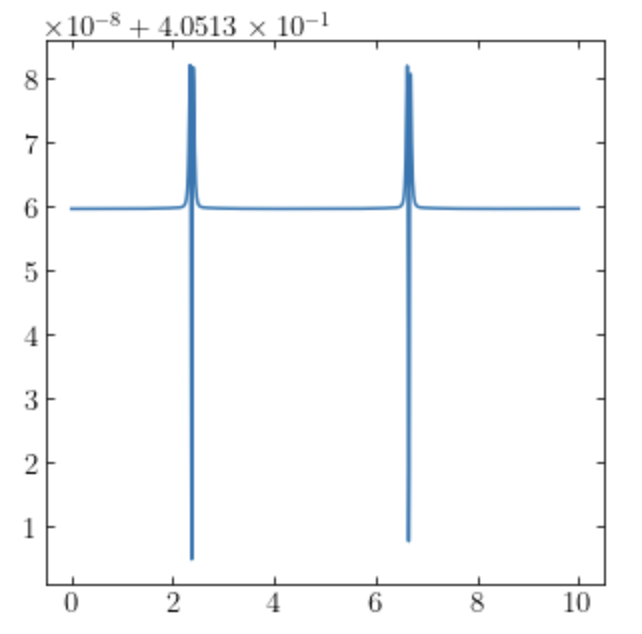

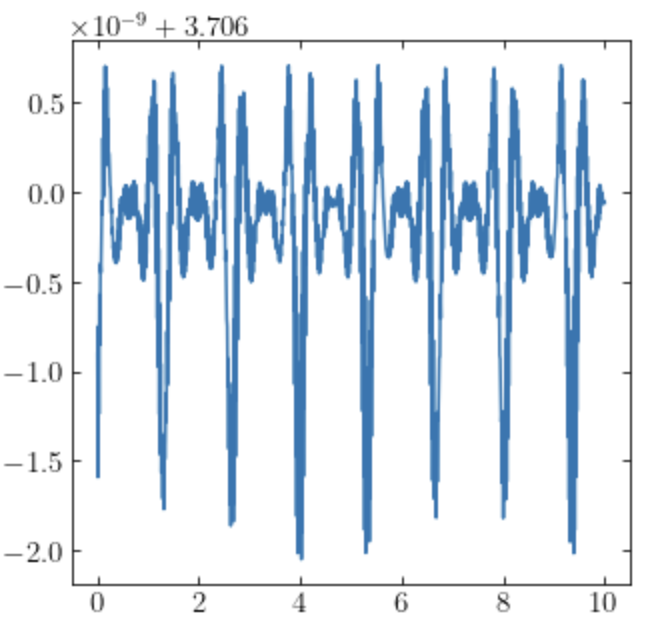

We can then check that the actions are constant over the orbit

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((jfa[0]-numpy.mean(jfa[0])))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((jfa[1]-numpy.mean(jfa[1])))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((jfa[2]-numpy.mean(jfa[2])))))

which gives

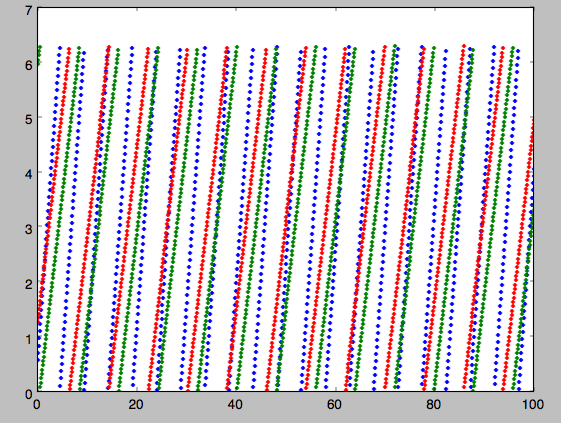

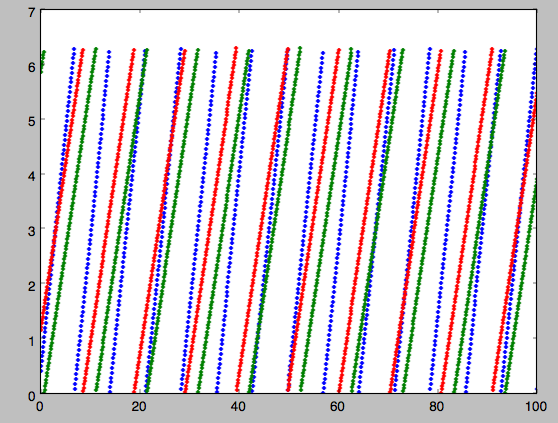

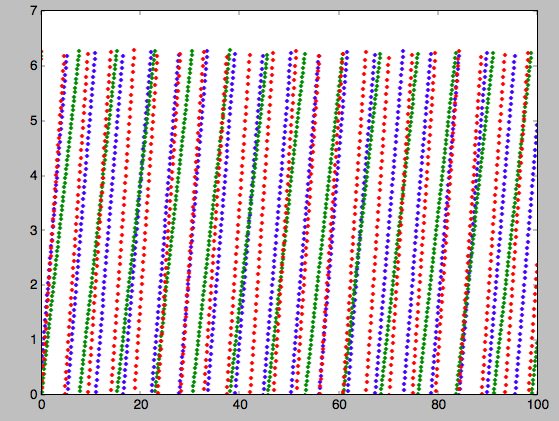

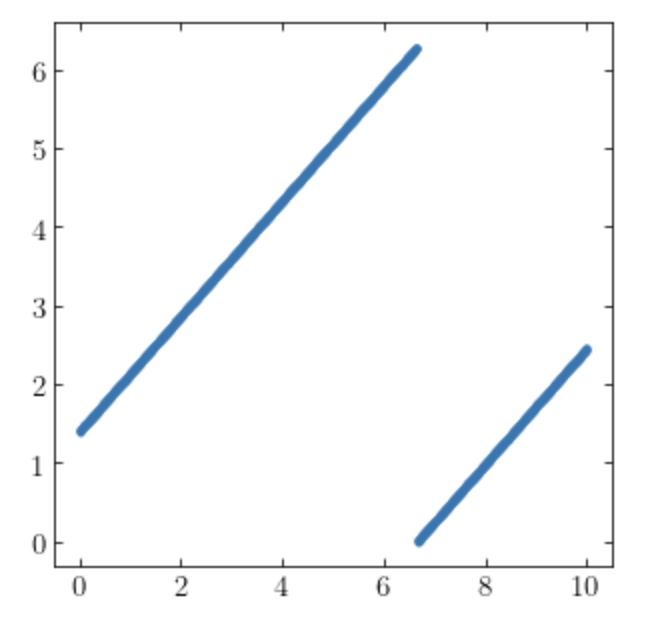

The actions are all conserved. The angles increase linearly with time

>>> plot(ts,jfa[6],'b.')

>>> plot(ts,jfa[7],'g.')

>>> plot(ts,jfa[8],'r.')

The reverse transformation is implemented as actionAngleIsochroneInverse.

For example, for the same isochrone potential as above, we set up the inverse

transformation as

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleIsochroneInverse

>>> aAII= actionAngleIsochroneInverse(ip=ip)

We can then reverse the transformation as follows:

>>> jr,jp,jz,oR,op,oz,ar,ap,az= aAI.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

>>> print(aAII(jr,jp,jz,ar,ap,az))

# (array([1.]), array([0.5]), array([1.3]), array([0.2]), array([0.1]), array([0.]))

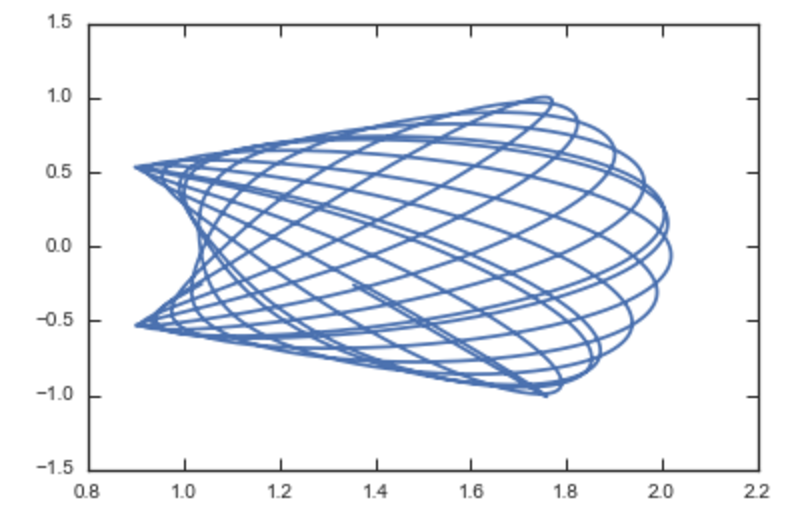

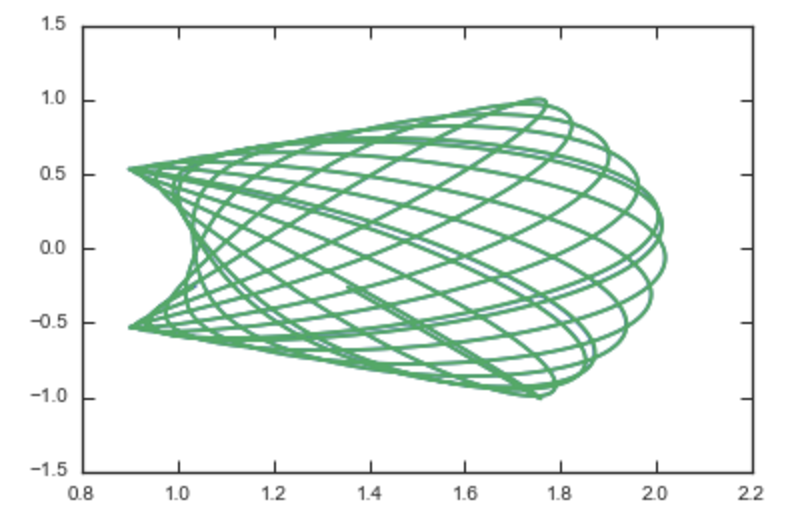

We can also do this for an entire orbit and compare to the orbit

>>> ar0,ap0,az0= 0.,0.,0.

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,10.,1001)

>>> ars,apz,azs= ar0+oR*ts, ap0+op*ts, az0+oz*ts

>>> xv= aAII(jr,jp,jz,ars,apz,azs)

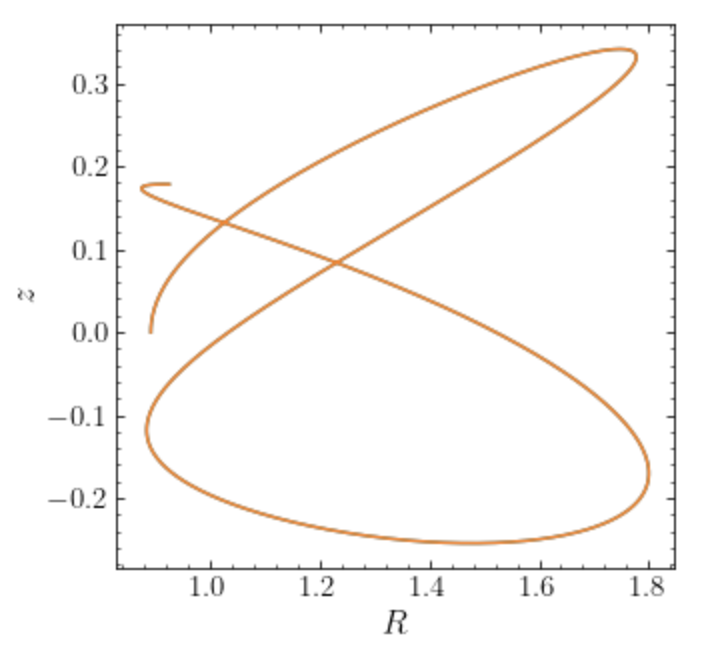

>>> plot(xv[0],xv[3])

>>> o= Orbit([xv[0][0],xv[1][0],xv[2][0],xv[3][0],xv[4][0],xv[5][0]])

>>> o.integrate(ts,ip)

>>> o.plot(gcf=True)

which gives

We see that the action-angle calculated orbit and the numerically-integrated orbit are right on top of each other.

For the 1D harmonic oscillator, do, e.g.,

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleHarmonic

>>> aAH= actionAngleHarmonic(omega=1.)

>>> print(aAH(1.,0.2))

# 0.52

>>> print(aAH.actionsFreqs(1.,0.2))

# (0.52, 1.0)

>>> print(aAH.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.2))

# (0.52, 1.0, 1.373400766945016)

We can also reverse this using actionAngleHarmonicInverse

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleHarmonicInverse

>>> aAHI= actionAngleHarmonicInverse(omega=1.)

>>> J,O,a= aAH.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.2)

>>> print(aAHI(J,a))

# (1.0, 0.19999999999999996)

UPDATED IN v1.8.2 Forward action-angle transformations (x, v) –> (J, O, a)¶

Action-angle coordinates for spherical potentials¶

Action-angle coordinates for any spherical potential can be calculated

using a few simple numerical integrations. These are implemented in galpy in the

actionAngleSpherical module. For example, we can do

>>> from galpy.potential import LogarithmicHaloPotential

>>> lp= LogarithmicHaloPotential(normalize=1.)

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleSpherical

>>> aAS= actionAngleSpherical(pot=lp)

For the same eccentric orbit as above we find

>>> aAS(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.22022112]), array([ 1.3]), array([ 0.02574507]))

>>> aAS.actionsFreqs(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.22022112]),

# array([ 1.3]),

# array([ 0.02574507]),

# array([ 0.87630459]),

# array([ 0.60872881]),

# array([ 0.60872881]))

>>> aAS.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.22022112]),

# array([ 1.3]),

# array([ 0.02574507]),

# array([ 0.87630459]),

# array([ 0.60872881]),

# array([ 0.60872881]),

# array([ 0.40443857]),

# array([ 5.85965048]),

# array([ 1.1472615]))

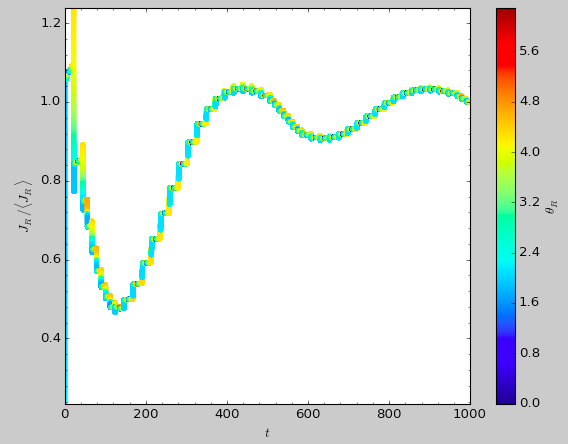

We can again check that the actions are conserved along the orbit and that the angles increase linearly with time:

>>> o.integrate(ts,lp)

>>> jfa= aAS.actionsFreqsAngles(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts),o.phi(ts),fixed_quad=True)

where we use fixed_quad=True for a faster evaluation of the

required one-dimensional integrals using Gaussian quadrature. We then

plot the action fluctuations

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((jfa[0]-numpy.mean(jfa[0])))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((jfa[1]-numpy.mean(jfa[1])))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((jfa[2]-numpy.mean(jfa[2])))))

which gives

showing that the actions are all conserved. The angles again increase linearly with time

>>> plot(ts,jfa[6],'b.')

>>> plot(ts,jfa[7],'g.')

>>> plot(ts,jfa[8],'r.')

We can check the spherical action-angle calculations against the analytical calculations for the isochrone potential. Starting again from the isochrone potential used in the previous section

>>> ip= IsochronePotential(b=1.,normalize=1.)

>>> aAI= actionAngleIsochrone(ip=ip)

>>> aAS= actionAngleSpherical(pot=ip)

we can compare the actions, frequencies, and angles computed using both

>>> aAI.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.13769498]),

# array([ 1.3]),

# array([ 0.02574507]),

# array([ 1.29136096]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.57101518]),

# array([ 5.96238847]),

# array([ 1.24999949]))

>>> aAS.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.)

# (array([ 0.13769498]),

# array([ 1.3]),

# array([ 0.02574507]),

# array([ 1.29136096]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.79093738]),

# array([ 0.57101518]),

# array([ 5.96238838]),

# array([ 1.2499994]))

or more explicitly comparing the two

>>> [r-s for r,s in zip(aAI.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.),aAS.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.5,1.3,0.2,0.1,0.))]

# [array([ 6.66133815e-16]),

# array([ 0.]),

# array([ 0.]),

# array([ -4.53851845e-10]),

# array([ 4.74775219e-10]),

# array([ 4.74775219e-10]),

# array([ -1.65965242e-10]),

# array([ 9.04759645e-08]),

# array([ 9.04759649e-08])]

Action-angle coordinates using the adiabatic approximation¶

For non-spherical, axisymmetric potentials galpy contains multiple methods for calculating approximate action–angle coordinates. The simplest of those is the adiabatic approximation, which works well for disk orbits that do not go too far from the plane, as it assumes that the vertical motion is decoupled from that in the plane (e.g., 2010MNRAS.401.2318B).

Setup is similar as for other actionAngle objects

>>> from galpy.potential import MWPotential2014

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleAdiabatic

>>> aAA= actionAngleAdiabatic(pot=MWPotential2014)

and evaluation then proceeds similarly as before

>>> aAA(1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.05)

# (0.01351896260559274, 1.1, 0.0004690133479435352)

We can again check that the actions are conserved along the orbit

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> ts=numpy.linspace(0.,100.,1001)

>>> o= Orbit([1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.05])

>>> o.integrate(ts,MWPotential2014)

>>> js= aAA(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts))

This takes a while. The adiabatic approximation is also implemented in C, which leads to great speed-ups. Here is how to use it

>>> timeit(aAA(1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.05))

# 10 loops, best of 3: 73.7 ms per loop

>>> aAA= actionAngleAdiabatic(pot=MWPotential2014,c=True)

>>> timeit(aAA(1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.05))

# 1000 loops, best of 3: 1.3 ms per loop

or about a 50 times speed-up. For arrays the speed-up is even more impressive

>>> s= numpy.ones(100)

>>> timeit(aAA(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 10 loops, best of 3: 37.8 ms per loop

>>> aAA= actionAngleAdiabatic(pot=MWPotential2014) #back to no C

>>> timeit(aAA(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 1 loops, best of 3: 7.71 s per loop

or a speed-up of 200! Back to the previous example, you can run it

with c=True to speed up the computation

>>> aAA= actionAngleAdiabatic(pot=MWPotential2014,c=True)

>>> js= aAA(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts))

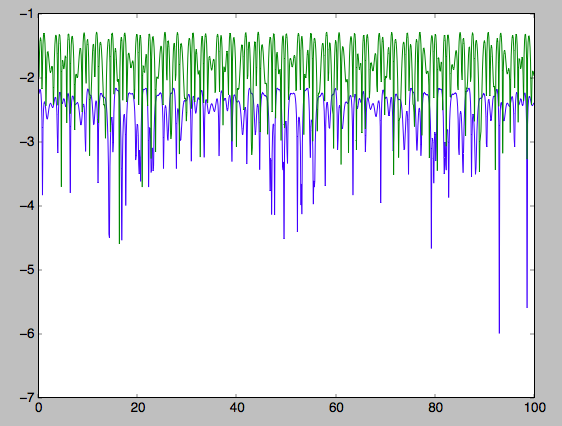

We can plot the radial- and vertical-action fluctuation as a function of time

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((js[0]-numpy.mean(js[0]))/numpy.mean(js[0]))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((js[2]-numpy.mean(js[2]))/numpy.mean(js[2]))))

which gives

The radial action is conserved to about half a percent, the vertical action to two percent.

Another way to speed up the calculation of actions using the adiabatic

approximation is to tabulate the actions on a grid in (approximate)

integrals of the motion and evaluating new actions by interpolating on

this grid. How this is done in practice is described in detail in the

galpy paper. To setup this grid-based interpolation method, which is

contained in actionAngleAdiabaticGrid, do

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleAdiabaticGrid

>>> aAG= actionAngleAdiabaticGrid(pot=MWPotential2014,nR=31,nEz=31,nEr=51,nLz=51,c=True)

where c=True specifies that we use the C implementation of

actionAngleAdiabatic for speed. We can now evaluate in the same

was as before, for example

>>> aAA(1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.05), aAG(1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.05)

# ((array([ 0.01352523]), array([ 1.1]), array([ 0.00046909])),

# (0.013527010324238781, 1.1, 0.00047747359874375148))

which agree very well. To look at the timings, we first switch back to not using C and then list all of the relevant timings:

>>> aAA= actionAngleAdiabatic(pot=MWPotential2014,c=False)

# Not using C, direct calculation

>>> timeit(aAA(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 1 loops, best of 3: 9.05 s per loop

>>> aAA= actionAngleAdiabatic(pot=MWPotential2014,c=True)

# Using C, direct calculation

>>> timeit(aAA(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 10 loops, best of 3: 39.7 ms per loop

# Grid-based calculation

>>> timeit(aAG(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 1000 loops, best of 3: 1.09 ms per loop

Thus, in this example (and more generally) the grid-based calculation

is significantly faster than even the direct implementation in C. The

overall speed up between the direct Python version and the grid-based

version is larger than 8,000; the speed up between the direct C

version and the grid-based version is 36. For larger arrays of input

phase-space positions, the latter speed up can increase to 150. For

simpler, fully analytical potentials the speed up will be slightly

less, but for MWPotential2014 and other more complicated

potentials (such as those involving a double-exponential disk), the

overhead of setting up the grid is worth it when evaluating more than

a few thousand actions.

The adiabatic approximation works well for orbits that stay close to the plane. The orbit we have been considering so far only reaches a height two percent of \(R_0\), or about 150 pc for \(R_0 = 8\) kpc.

>>> o.zmax()*8.

# 0.17903686455491979

For orbits that reach distances of a kpc and more from the plane, the adiabatic approximation does not work as well. For example,

>>> o= Orbit([1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.25])

>>> o.integrate(ts,MWPotential2014)

>>> o.zmax()*8.

# 1.3506059038621048

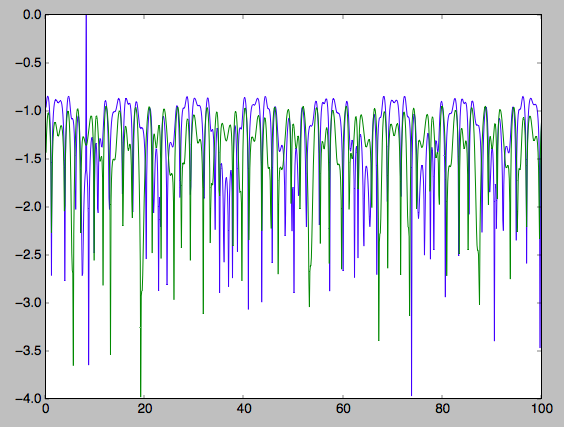

and we can again calculate the actions along the orbit

>>> js= aAA(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((js[0]-numpy.mean(js[0]))/numpy.mean(js[0]))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((js[2]-numpy.mean(js[2]))/numpy.mean(js[2]))))

which gives

The radial action is now only conserved to about ten percent and the vertical action to approximately five percent.

Warning

Frequencies and angles using the adiabatic approximation are not implemented at this time.

Action-angle coordinates using the Staeckel approximation¶

A better approximation than the adiabatic one is to locally approximate the potential as a Staeckel potential, for which actions, frequencies, and angles can be calculated through numerical integration. galpy contains an implementation of the algorithm of Binney (2012; 2012MNRAS.426.1324B), which accomplishes the Staeckel approximation for disk-like (i.e., oblate) potentials without explicitly fitting a Staeckel potential. For all intents and purposes the adiabatic approximation is made obsolete by this new method, which is as fast and more precise. The only advantage of the adiabatic approximation over the Staeckel approximation is that the Staeckel approximation requires the user to specify a focal length \(\Delta\) to be used in the Staeckel approximation. However, this focal length can be easily estimated from the second derivatives of the potential (see Sanders 2012; 2012MNRAS.426..128S).

Starting from the second orbit example in the adiabatic section above,

we first estimate a good focal length of the MWPotential2014 to

use in the Staeckel approximation. We do this by averaging (through

the median) estimates at positions around the orbit (which we

integrated in the example above)

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import estimateDeltaStaeckel

>>> estimateDeltaStaeckel(MWPotential2014,o.R(ts),o.z(ts))

# 0.40272708556203662

We will use \(\Delta = 0.4\) in what follows. We set up the

actionAngleStaeckel object

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleStaeckel

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,c=False) #c=True is the default

and calculate the actions

>>> aAS(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz())

# (0.019212848866725911, 1.1000000000000001, 0.015274597971510892)

The adiabatic approximation from above gives

>>> aAA(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz())

# (array([ 0.01686478]), array([ 1.1]), array([ 0.01590001]))

The actionAngleStaeckel calculations are sped up in two ways. First,

the action integrals can be calculated using Gaussian quadrature by

specifying fixed_quad=True

>>> aAS(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz(),fixed_quad=True)

# (0.01922167296633687, 1.1000000000000001, 0.015276825017286706)

which in itself leads to a ten times speed up

>>> timeit(aAS(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz(),fixed_quad=False))

# 10 loops, best of 3: 129 ms per loop

>>> timeit(aAS(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz(),fixed_quad=True))

# 100 loops, best of 3: 10.3 ms per loop

Second, the actionAngleStaeckel calculations have also been implemented in C, which leads to even greater speed-ups, especially for arrays

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,c=True)

>>> s= numpy.ones(100)

>>> timeit(aAS(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 10 loops, best of 3: 35.1 ms per loop

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,c=False) #back to no C

>>> timeit(aAS(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s,fixed_quad=True))

# 1 loops, best of 3: 496 ms per loop

or a fifteen times speed up. The speed up is not that large because

the bulge model in MWPotential2014 requires expensive special

functions to be evaluated. Computations could be sped up ten times

more when using a simpler bulge model.

Similar to actionAngleAdiabaticGrid, we can also tabulate the

actions on a grid of (approximate) integrals of the motion and

interpolate over this look-up table when evaluating new actions. The

details of how this look-up table is setup and used are again fully

explained in the galpy paper. To use this grid-based Staeckel

approximation, contained in actionAngleStaeckelGrid, do

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleStaeckelGrid

>>> aASG= actionAngleStaeckelGrid(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,nE=51,npsi=51,nLz=61,c=True)

where c=True makes sure that we use the C implementation of the

Staeckel method to calculate the grid. Because this is a fully

three-dimensional grid, setting up the grid takes longer than it does

for the adiabatic method (which only uses two two-dimensional

grids). We can then evaluate actions as before

>>> aAS(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz()), aASG(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz())

# ((0.019212848866725911, 1.1000000000000001, 0.015274597971510892),

# (0.019221119033345408, 1.1000000000000001, 0.015022528662310393))

These actions agree very well. We can compare the timings of these methods as above

>>> timeit(aAS(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s,fixed_quad=True))

# 1 loops, best of 3: 576 ms per loop # Not using C, direct calculation

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,c=True)

>>> timeit(aAS(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 100 loops, best of 3: 17.8 ms per loop # Using C, direct calculation

>>> timeit(aASG(1.*s,0.1*s,1.1*s,0.*s,0.05*s))

# 100 loops, best of 3: 3.45 ms per loop # Grid-based calculation

This demonstrates that the grid-based interpolation again leeds to a

significant speed up, even over the C implementation of the direct

calculation. This speed up becomes more significant for larger array

input, although it saturates at about 25 times (at least for

MWPotential2014).

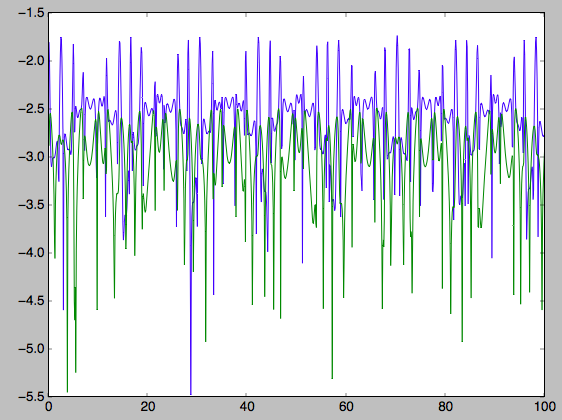

We can now go back to checking that the actions are conserved along

the orbit (going back to the c=False version of

actionAngleStaeckel)

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,c=False)

>>> js= aAS(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts),fixed_quad=True)

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((js[0]-numpy.mean(js[0]))/numpy.mean(js[0]))))

>>> plot(ts,numpy.log10(numpy.fabs((js[2]-numpy.mean(js[2]))/numpy.mean(js[2]))))

which gives

The radial action is now conserved to better than a percent and the vertical action to only a fraction of a percent. Clearly, this is much better than the five to ten percent errors found for the adiabatic approximation above.

For the Staeckel approximation we can also calculate frequencies and

angles through the actionsFreqs and actionsFreqsAngles

methods.

Warning

Frequencies and angles using the Staeckel approximation

are only implemented in C. So use c=True in the setup of the

actionAngleStaeckel object.

Warning

Angles using the Staeckel approximation in galpy are such that (a) the radial angle starts at zero at pericenter and increases then going toward apocenter; (b) the vertical angle starts at zero at z=0 and increases toward positive zmax. The latter is a different convention from that in Binney (2012), but is consistent with that in actionAngleIsochrone and actionAngleSpherical.

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=MWPotential2014,delta=0.4,c=True)

>>> o= Orbit([1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.25,0.]) #need to specify phi for angles

>>> aAS.actionsFreqsAngles(o.R(),o.vR(),o.vT(),o.z(),o.vz(),o.phi())

# (array([ 0.01922167]),

# array([ 1.1]),

# array([ 0.01527683]),

# array([ 1.11317796]),

# array([ 0.82538032]),

# array([ 1.34126138]),

# array([ 0.37758087]),

# array([ 6.17833493]),

# array([ 6.13368239]))

and we can check that the angles increase linearly along the orbit

>>> o.integrate(ts,MWPotential2014)

>>> jfa= aAS.actionsFreqsAngles(o.R(ts),o.vR(ts),o.vT(ts),o.z(ts),o.vz(ts),o.phi(ts))

>>> plot(ts,jfa[6],'b.')

>>> plot(ts,jfa[7],'g.')

>>> plot(ts,jfa[8],'r.')

or

>>> plot(jfa[6],jfa[8],'b.')

Action-angle coordinates using an orbit-integration-based approximation¶

The adiabatic and Staeckel approximations used above are good for stars on close-to-circular orbits, but they break down for more eccentric orbits (specifically, orbits for which the radial and/or vertical action is of a similar magnitude as the angular momentum). This is because the approximations made to the potential in these methods (that it is separable in R and z for the adiabatic approximation and that it is close to a Staeckel potential for the Staeckel approximation) break down for such orbits. Unfortunately, these methods cannot be refined to provide better approximations for eccentric orbits.

galpy contains a new method for calculating actions, frequencies, and angles that is completely general for any static potential. It can calculate the actions to any desired precision for any orbit in such potentials. The method works by employing an auxiliary isochrone potential and calculates action-angle variables by arithmetic operations on the actions and angles calculated in the auxiliary potential along an orbit (integrated in the true potential). Full details can be found in Appendix A of Bovy (2014).

We setup this method for a logarithmic potential as follows

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleIsochroneApprox

>>> from galpy.potential import LogarithmicHaloPotential

>>> lp= LogarithmicHaloPotential(normalize=1.,q=0.9)

>>> aAIA= actionAngleIsochroneApprox(pot=lp,b=0.8)

b=0.8 here sets the scale parameter of the auxiliary isochrone

potential; this potential can also be specified as an

IsochronePotential instance through ip=). We can now calculate the

actions for an orbit similar to that of the GD-1 stream

>>> obs= numpy.array([1.56148083,0.35081535,-1.15481504,0.88719443,-0.47713334,0.12019596]) #orbit similar to GD-1

>>> aAIA(*obs)

# (array([ 0.16605011]), array([-1.80322155]), array([ 0.50704439]))

An essential requirement of this method is that the angles calculated in the auxiliary potential go through the full range \([0,2\pi]\). If this is not the case, galpy will raise a warning

>>> aAIA= actionAngleIsochroneApprox(pot=lp,b=10.8)

>>> aAIA(*obs)

# galpyWarning: Full radial angle range not covered for at least one object; actions are likely not reliable

# (array([ 0.08985167]), array([-1.80322155]), array([ 0.50849276]))

Therefore, some care should be taken to choosing a good auxiliary

potential. galpy contains a method to estimate a decent scale

parameter for the auxiliary scale parameter, which works similar to

estimateDeltaStaeckel above except that it also gives a minimum

and maximum b if multiple R and z are given

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import estimateBIsochrone

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> o= Orbit(obs)

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,100.,1001)

>>> o.integrate(ts,lp)

>>> estimateBIsochrone(lp,o.R(ts),o.z(ts))

# (0.78065062339131952, 1.2265541473461612, 1.4899326335155412) #bmin,bmedian,bmax over the orbit

Experience shows that a scale parameter somewhere in the range returned by this function makes sure that the angles go through the full \([0,2\pi]\) range. However, even if the angles go through the full range, the closer the angles increase to linear, the better the converenge of the algorithm is (and especially, the more accurate the calculation of the frequencies and angles is, see below). For example, for the scale parameter at the upper and of the range

>>> aAIA= actionAngleIsochroneApprox(pot=lp,b=1.5)

>>> aAIA(*obs)

# (array([ 0.01120145]), array([-1.80322155]), array([ 0.50788893]))

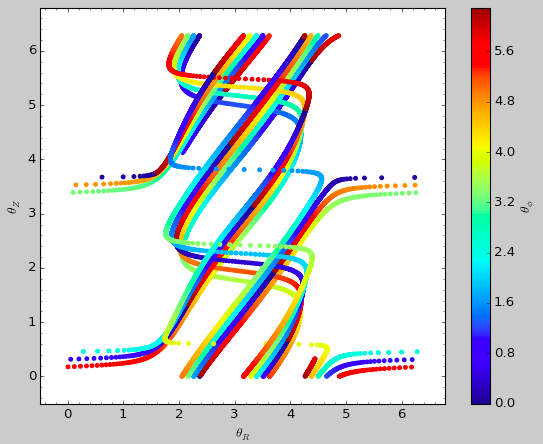

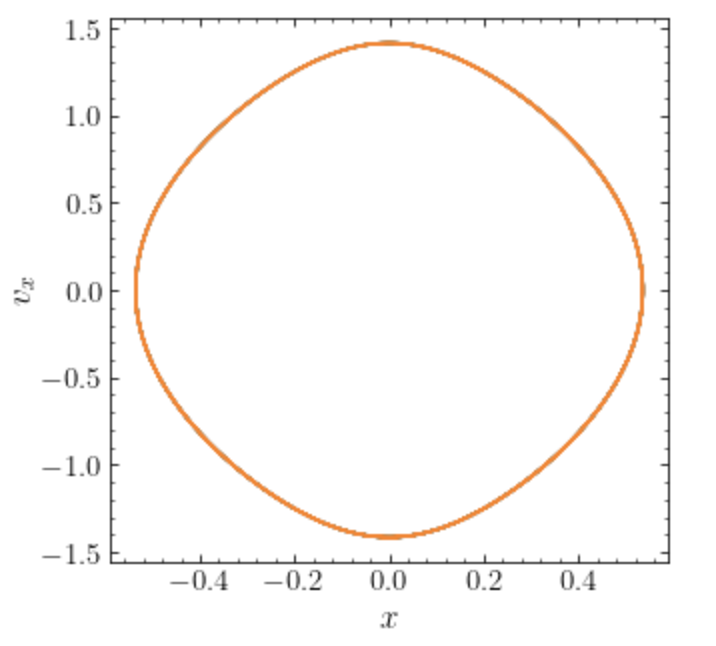

which does not agree with the previous calculation. We can inspect how

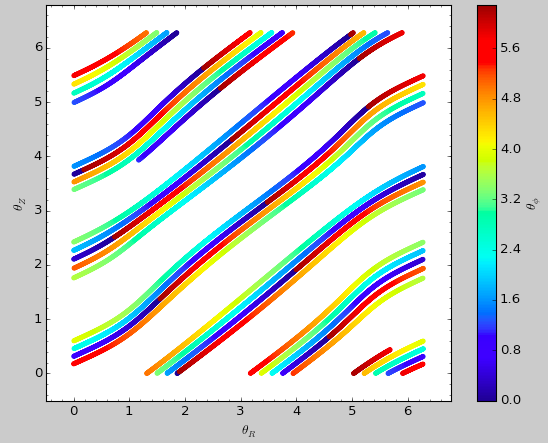

the angles increase and how the actions converge by using the

aAIA.plot function. For example, we can plot the radial versus the

vertical angle in the auxiliary potential

>>> aAIA.plot(*obs,type='araz')

which gives

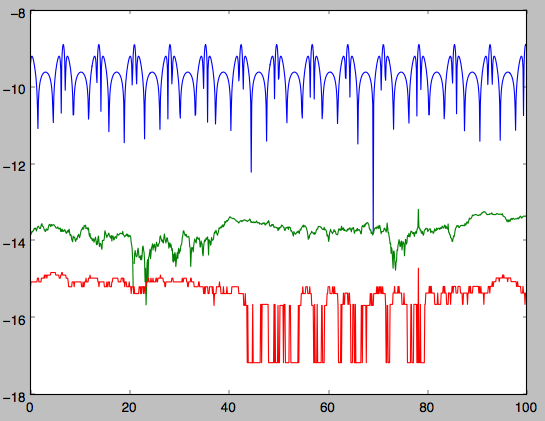

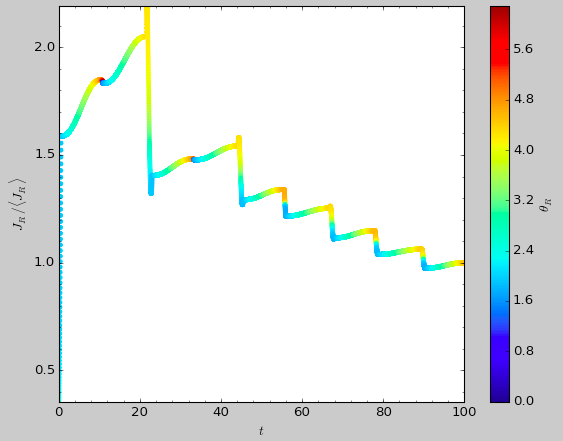

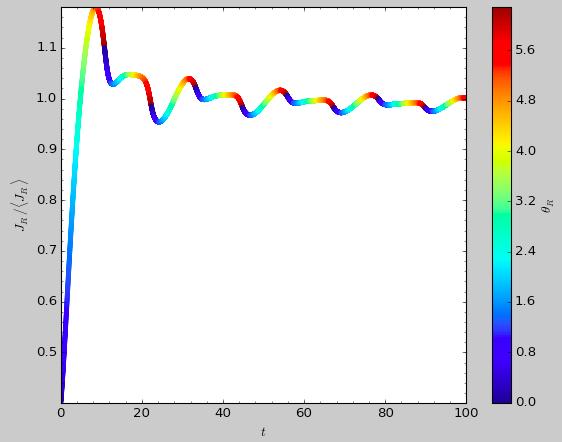

and this clearly shows that the angles increase very non-linearly, because the auxiliary isochrone potential used is too far from the real potential. This causes the actions to converge only very slowly. For example, for the radial action we can plot the converge as a function of integration time

>>> aAIA.plot(*obs,type='jr')

which gives

This Figure clearly shows that the radial action has not converged yet. We need to integrate much longer in this auxiliary potential to obtain convergence and because the angles increase so non-linearly, we also need to integrate the orbit much more finely:

>>> aAIA= actionAngleIsochroneApprox(pot=lp,b=1.5,tintJ=1000,ntintJ=800000)

>>> aAIA(*obs)

# (array([ 0.01711635]), array([-1.80322155]), array([ 0.51008058]))

>>> aAIA.plot(*obs,type='jr')

which shows slow convergence

Finding a better auxiliary potential makes convergence much faster

and also allows the frequencies and the angles to be calculated by

removing the small wiggles in the auxiliary angles vs. time (in the

angle plot above, the wiggles are much larger, such that removing them

is hard). The auxiliary potential used above had b=0.8, which

shows very quick converenge and good behavior of the angles

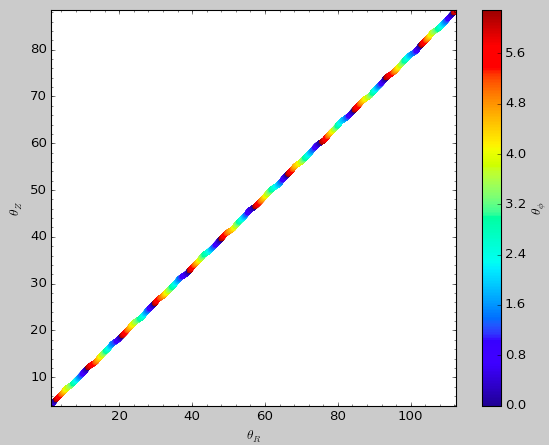

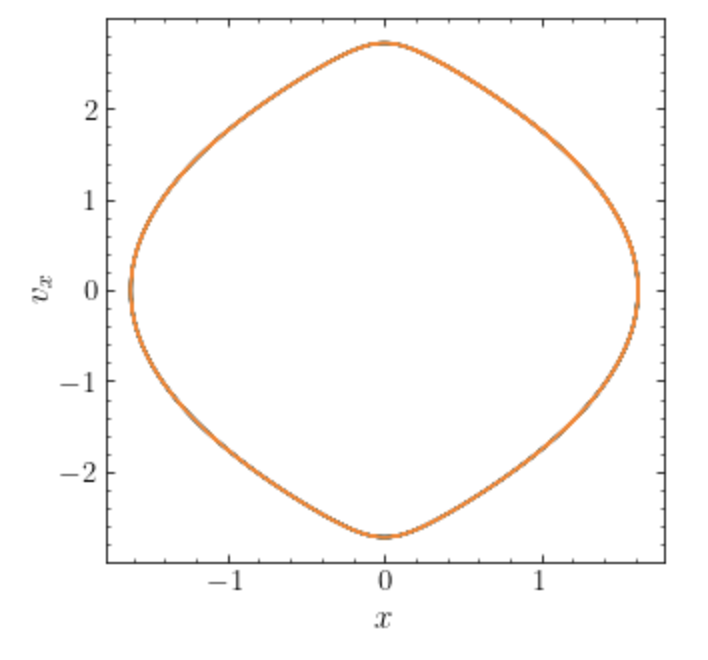

>>> aAIA= actionAngleIsochroneApprox(pot=lp,b=0.8)

>>> aAIA.plot(*obs,type='jr')

gives

and

>>> aAIA.plot(*obs,type='araz')

gives

We can remove the periodic behavior from the angles, which clearly shows that they increase close-to-linear with time

>>> aAIA.plot(*obs,type='araz',deperiod=True)

We can then calculate the frequencies and the angles for this orbit as

>>> aAIA.actionsFreqsAngles(*obs)

# (array([ 0.16392384]),

# array([-1.80322155]),

# array([ 0.50999882]),

# array([ 0.55808933]),

# array([-0.38475753]),

# array([ 0.42199713]),

# array([ 0.18739688]),

# array([ 0.3131815]),

# array([ 2.18425661]))

This function takes as an argument maxn= the maximum n for which

to remove sinusoidal wiggles. So we can raise this, for example to 4

from 3

>>> aAIA.actionsFreqsAngles(*obs,maxn=4)

# (array([ 0.16392384]),

# array([-1.80322155]),

# array([ 0.50999882]),

# array([ 0.55808776]),

# array([-0.38475733]),

# array([ 0.4219968]),

# array([ 0.18732009]),

# array([ 0.31318534]),

# array([ 2.18421296]))

Clearly, there is very little change, as most of the wiggles are of low n.

This technique also works for triaxial potentials, but using those

requires the code to also use the azimuthal angle variable in the

auxiliary potential (this is unnecessary in axisymmetric potentials as

the z component of the angular momentum is conserved). We can

calculate actions for triaxial potentials by specifying that

nonaxi=True:

>>> aAIA(*obs,nonaxi=True)

# (array([ 0.16605011]), array([-1.80322155]), array([ 0.50704439]))

Action-angle coordinates for one dimensional potentials¶

As for spherical potentials, actions, frequencies, and angles can be computed for any one-dimensional potential using a few simple numerical integrals. In the context of galactic dynamics, this is, for example, useful for studying the dynamical in the vertical direction perpendicular to the main plane of a disk.

The action-angle coordinates for one-dimensional potentials are computed using the

actionAngleVertical class. This class can be initialized with a

linearPotential instance or with a list of such instances

(verticalPotential instances which represent the vertical direction of

3D potentials are examples of a linearPotential). As an example, we’ll

consider orbits in the one-dimensional version of the MWPotential2014 model

>>> from galpy.potential import MWPotential2014, toVerticalPotential

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleVertical

>>> pot= toVerticalPotential(MWPotential2014,1.) # vertical potential at R=1.

>>> aAV= actionAngleVertical(pot=pot)

Now we can compute the actions, frequencies, and angles using the usual set of methods:

>>> aAV.actionsFreqsAngles(1.,0.1)

# (array([0.40513006]), array([0.73363198]), array([1.40229361]))

To check the accuracy of the 1D action-angle coordinates, we can compute them along an orbit

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> o= Orbit([1.,0.1])

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,10.,1001)

>>> o.integrate(ts,pot)

>>> plot(ts,aAV(o.x(ts),o.vx(ts)))

which gives

The angles increase linearly with time

>>> plot(ts,aAV.actionsFreqsAngles(o.x(ts),o.vx(ts))[2],'.')

which gives

UPDATED IN v1.8.2 Reverse action-angle transformations (J, a) –> (x, v, O)¶

Reverse action-angle transformations for one-dimensional potentials¶

The actionAngleVerticalInverse class also allows to compute the phase-space

coordinates for given actions and angles in one-dimensional potentials. This

uses a robust root-finding/Fourier-transformation implementation of the torus

mapping algorithm that can optionally use a point-transformation to improve the

quality of the transformation (Bovy in prep. who knows). As an example, we use

a simple IsothermalDiskPotential:

>>> from galpy.potential import IsothermalDiskPotential

>>> isopot= IsothermalDiskPotential(amp=1.,sigma=0.5)

We then set up the actionAngleVerticalInverse object, e.g., to only reverse

the transformation for three values of the energy:

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleVerticalInverse

>>> aA1Dinv= actionAngleVerticalInverse(pot=isopot,nta=4*128,

Es=[0.1,1.,10.],

use_pointtransform=False)

Let’s then compute an orbit using the reverse transformation. First, we obtain

the frequency, e.g., for the E=1. orbit (note that the input to this method

is action, so we use aA1Dinv.J to convert energy to action):

>>> O= aA1Dinv.Freqs(aA1Dinv.J(1.))

Then we integrate an orbit

>>> a0= 0.1

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,10.,1001)

>>> angles= a0+O*ts

>>> xv= aA1Dinv(aA1Dinv.J(1.),angles)

>>> plot(xv[0],xv[1])

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> o= Orbit([xv[0][0],xv[1][0]])

>>> o.integrate(ts,isopot)

>>> o.plot(gcf=True)

which gives

To be able to reverse the action-angle transformation for many orbits, we can set up the instance so it supports interpolation between the tori at which the reverse transformation is computed. This can be done as follows

>>> aA1Dinv= actionAngleVerticalInverse(pot=isopot,nta=2*128,

Es=numpy.linspace(0.,4.,1001),

setup_interp=True,

use_pointtransform=True,pt_deg=7)

where we have also used a point transformation. Now we can compute the reverse transformation at any orbit within the energy range, e.g.,

>>> a0= 0.1

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,10.,1001)

>>> angles= a0+O*ts

>>> xv= aA1Dinv(aA1Dinv.J(3.706),angles) # between grid points

>>> plot(xv[0],xv[1])

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> o= Orbit([xv[0][0],xv[1][0]])

>>> o.integrate(ts,isopot)

>>> o.plot(gcf=True)

which gives

Energy conservation is very good

>>> from galpy.potential import evaluatelinearPotentials

>>> plot(ts,xv[1]**2./2.+evaluatelinearPotentials(isopot,xv[0]))

gives

Action-angle coordinates using the TorusMapper code¶

galpy also contains some support for computing the reverse action-angle

transformation for general axisymmetric potentials using an interface to the

TorusMapper code. Currently,

this is limited to axisymmetric potentials, because the TorusMapper code is

limited to such potentials.

The basic use of this part of galpy is to compute an orbit

\((R,v_R,v_T,z,v_z,\phi)\) for a given torus, specified by three

actions \((J_R,L_Z,J_Z)\) and as many angles along a torus as you

want. First we set up an actionAngleTorus object

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleTorus

>>> from galpy.potential import MWPotential2014

>>> aAT= actionAngleTorus(pot=MWPotential2014)

To compute an orbit, we first need to compute the frequencies, which we do as follows

>>> jr,lz,jz= 0.1,1.1,0.2

>>> Om= aAT.Freqs(jr,lz,jz)

This set consists of \((\Omega_R,\Omega_\phi,\Omega_Z,\mathrm{TM err})\), where the last entry is the exit code of the TorusMapper code (will be printed as a warning when it is non-zero). Then we compute a set of angles that fall along an orbit as \(\mathbf{\theta}(t) = \mathbf{\theta}_0+\mathbf{\Omega}\,t\) for a set of times \(t\)

>>> times= numpy.linspace(0.,100.,10001)

>>> init_angle= numpy.array([1.,2.,3.])

>>> angles= numpy.tile(init_angle,(len(times),1))+Om[:3]*numpy.tile(times,(3,1)).T

Then we can compute the orbit by transforming the orbit in action-angle coordinates to configuration space as follows

>>> RvR,_,_,_,_= aAT.xvFreqs(jr,lz,jz,angles[:,0],angles[:,1],angles[:,2])

Note that the frequency is also always computed and returned by this

method, because it can be obtained at zero cost. The RvR array has

shape (ntimes,6) and the six phase-space coordinates are arranged

in the usual (R,vR,vT,z,vz,phi) order. The orbit in \((R,Z)\)

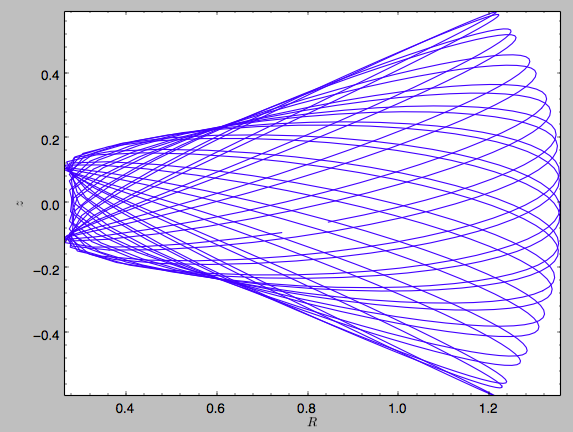

is then given by

>>> plot(RvR[:,0],RvR[:,3])

We can compare this to the direct numerical orbit integration. We

integrate the orbit, starting at the position and velocity of the

initial angle RvR[0]

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> orb= Orbit(RvR[0])

>>> orb.integrate(times,MWPotential2014)

>>> orb.plot(overplot=True)

The two orbits are exactly the same.

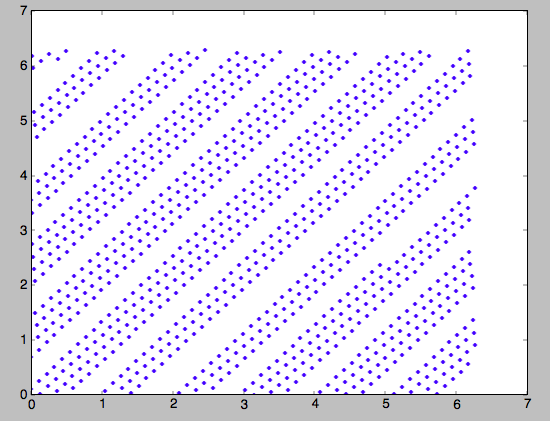

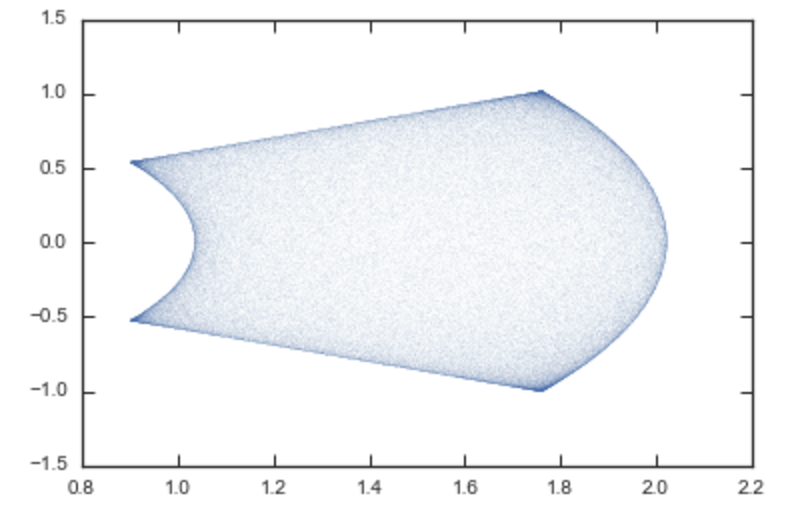

Of course, we do not have to follow the path of an orbit to map the entire orbital torus and thus reveal the orbital building blocks of galaxies. To directly map a torus, we can do (don’t worry, this doesn’t take very long)

>>> nangles= 200001

>>> angler= numpy.random.uniform(size=nangles)*2.*numpy.pi

>>> anglep= numpy.random.uniform(size=nangles)*2.*numpy.pi

>>> anglez= numpy.random.uniform(size=nangles)*2.*numpy.pi

>>> RvR,_,_,_,_= aAT.xvFreqs(jr,lz,jz,angler,anglep,anglez)

>>> plot(RvR[:,0],RvR[:,3],',',alpha=0.02)

which directly shows where the orbit spends most of its time:

actionAngleTorus has additional methods documented on the

action-angle API page for computing Hessians and Jacobians of the

transformation between action-angle and configuration space

coordinates.

Accessing action-angle coordinates for Orbit instances¶

While the most flexible way to access the actionAngle routines is

through the methods in the galpy.actionAngle modules, action-angle

coordinates can also be calculated for galpy.orbit.Orbit instances

and this is often more convenient. This is illustrated here

briefly. We initialize an Orbit instance

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> from galpy.potential import MWPotential2014

>>> o= Orbit([1.,0.1,1.1,0.,0.25,0.])

and we can then calculate the actions (default is to use the staeckel approximation with an automatically-estimated delta parameter, but this can be adjusted)

>>> o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014), o.jp(pot=MWPotential2014), o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014)

# (0.018194068808944613,1.1,0.01540155584446606)

o.jp here gives the azimuthal action (which is the z component

of the angular momentum for axisymmetric potentials). We can also use

the other methods described above or adjust the parameters of the

approximation (see above):

>>> o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4), o.jp(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4), o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4)

# (0.019221672966336707, 1.1, 0.015276825017286827)

>>> o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='adiabatic'), o.jp(pot=MWPotential2014,type='adiabatic'), o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014,type='adiabatic')

# (0.016856430059017123, 1.1, 0.015897730620467752)

>>> o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8), o.jp(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8), o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8)

# (0.019066091295488922, 1.1, 0.015280492319332751)

These two methods give very precise actions for this orbit (both are converged to about 1%) and they agree very well

>>> (o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4)-o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8))/o.jr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8)

# 0.00816012408818143

>>> (o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4)-o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8))/o.jz(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8)

# 0.00023999894566772273

We can also calculate the frequencies and the angles. This requires using the Staeckel or Isochrone approximations, because frequencies and angles are currently not supported for the adiabatic approximation. For example, the radial frequency

>>> o.Or(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4)

# 1.1131779637307115

>>> o.Or(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8)

# 1.1134635974560649

and the radial angle

>>> o.wr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='staeckel',delta=0.4)

# 0.37758086786371969

>>> o.wr(pot=MWPotential2014,type='isochroneApprox',b=0.8)

# 0.38159809018175395

which again agree to 1%. We can also calculate the other frequencies,

angles, as well as periods using the functions o.Op, o.oz,

o.wp, o.wz, o.Tr, o.Tp, o.Tz.

All of the functions above also work for Orbit instances that

contain multiple objects. This is particularly convenient if you have

data in observed coordinates (e.g., RA, Dec, etc.), for example,

>>> numpy.random.seed(1)

>>> nrand= 30

>>> ras= numpy.random.uniform(size=nrand)*360.*u.deg

>>> decs= 90.*(2.*numpy.random.uniform(size=nrand)-1.)*u.deg

>>> dists= numpy.random.uniform(size=nrand)*10.*u.kpc

>>> pmras= 2.*(2.*numpy.random.uniform(size=nrand)-1.)*u.mas/u.yr

>>> pmdecs= 2.*(2.*numpy.random.uniform(size=nrand)-1.)*u.mas/u.yr

>>> vloss= 200.*(2.*numpy.random.uniform(size=nrand)-1.)*u.km/u.s

>>> co= SkyCoord(ra=ras,dec=decs,distance=dists,

pm_ra_cosdec=pmras,pm_dec=pmdecs,

radial_velocity=vloss,

frame='icrs')

>>> orbits= Orbit(co)

>>> orbits.jr(pot=MWPotential2014)

# [2363.7957, 360.12445, 690.32238, 1046.2924, 132.9572, 86.989812, 272.06487, 360.73566, 55.568238, 698.18447, 24.783574, 21.889352, 16.148216, 3870.4286, 743.63456, 317.66551, 325.93816, 183.86429, 56.087796, 180.42838, 1121.8019, 8700.8335, 977.8525, 7.569396, 8.2847477, 210.72127, 160.9785, 680.63864, 1093.7413, 87.629873]kmkpcs

Example: Evidence for a Lindblad resonance in the Solar neighborhood¶

We can use galpy to calculate action-angle coordinates for a set of

stars in the Solar neighborhood and look for unexplained features. For

this we download the data from the Geneva-Copenhagen Survey

(2009A&A…501..941H; data available

at viZier). Since

the velocities in this catalog are given as U,V, and W, we use the

radec and UVW keywords to initialize the orbits from the raw

data. For each object ii

>>> o= Orbit(vxvv[ii,:],radec=True,uvw=True,vo=220.,ro=8.)

We then calculate the actions and angles for each object in a flat rotation curve potential

>>> lp= LogarithmicHaloPotential(normalize=1.)

>>> myjr[ii]= o.jr(lp)

etc.

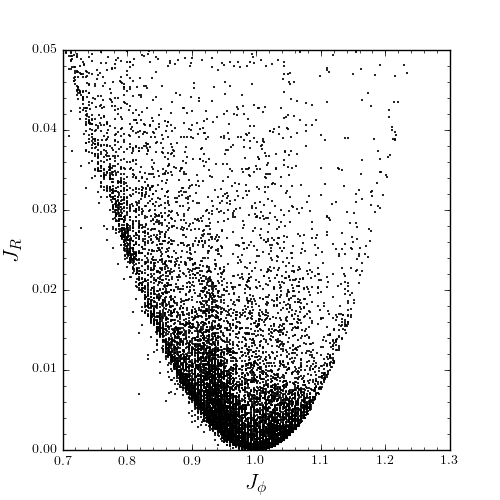

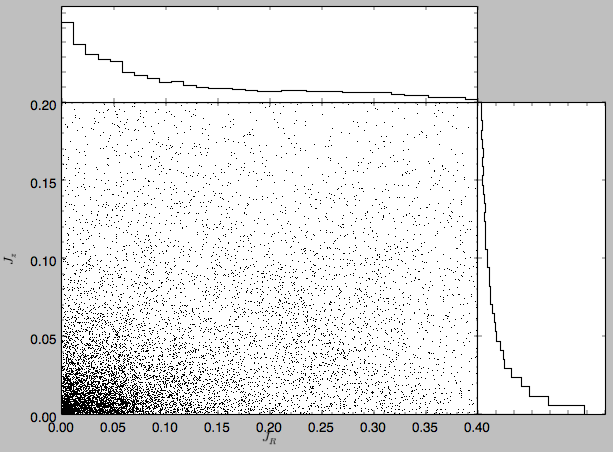

Plotting the radial action versus the angular momentum

>>> import galpy.util.plot as galpy_plot

>>> galpy_plot.plot(myjp,myjr,'k.',ms=2.,xlabel=r'$J_{\phi}$',ylabel=r'$J_R$',xrange=[0.7,1.3],yrange=[0.,0.05])

shows a feature in the distribution

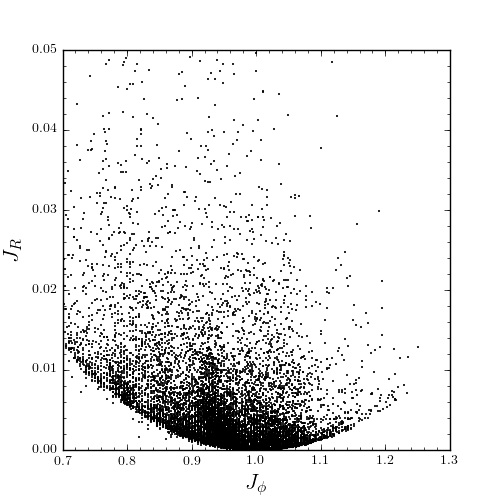

If instead we use a power-law rotation curve with power-law index 1

>>> pp= PowerSphericalPotential(normalize=1.,alpha=-2.)

>>> myjr[ii]= o.jr(pp)

We find that the distribution is stretched, but the feature remains

Code for this example can be found here (note that this code uses a particular

download of the GCS data set; if you use your own version, you will

need to modify the part of the code that reads the data). For more

information see 2010MNRAS.409..145S.

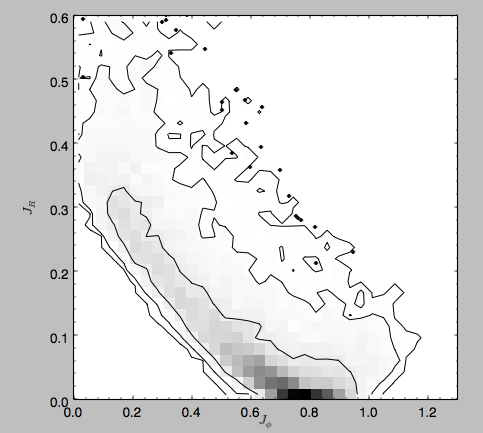

Example: actions in an N-body simulation¶

To illustrate how we can use galpy to calculate actions in a

snapshot of an N-body simulation, we again look at the g15784

snapshot in the pynbody test suite, discussed in The

potential of N-body simulations. Please look at that

section for information on how to setup the potential of this snapshot

in galpy. One change is that we should set enable_c=True in

the instantiation of the InterpSnapshotRZPotential object

>>> spi= InterpSnapshotRZPotential(h1,rgrid=(numpy.log(0.01),numpy.log(20.),101),logR=True,zgrid=(0.,10.,101),interpPot=True,zsym=True,enable_c=True)

>>> spi.normalize(R0=10.)

where we again normalize the potential to use galpy’s natural units.

We first load a pristine copy of the simulation (because the normalization above leads to some inconsistent behavior in pynbody)

>>> sc = pynbody.load('Repos/pynbody-testdata/g15784.lr.01024.gz'); hc = sc.halos(); hc1= hc[1]; pynbody.analysis.halo.center(hc1,mode='hyb'); pynbody.analysis.angmom.faceon(hc1, cen=(0,0,0),mode='ssc'); sc.physical_units()

and then select particles near R=8 kpc by doing

>>> sn= pynbody.filt.BandPass('rxy','7 kpc','9 kpc')

>>> R,vR,vT,z,vz = [numpy.ascontiguousarray(hc1.s[sn][x]) for x in ('rxy','vr','vt','z','vz')]

These have physical units, so we normalize them (the velocity

normalization is the circular velocity at R=10 kpc, see

here).

>>> ro, vo= 10., 294.62723076942245

>>> R/= ro

>>> z/= ro

>>> vR/= vo

>>> vT/= vo

>>> vz/= vo

We will calculate actions using actionAngleStaeckel above. We can

first integrate a random orbit in this potential

>>> from galpy.orbit import Orbit

>>> numpy.random.seed(1)

>>> ii= numpy.random.permutation(len(R))[0]

>>> o= Orbit([R[ii],vR[ii],vT[ii],z[ii],vz[ii]])

>>> ts= numpy.linspace(0.,100.,1001)

>>> o.integrate(ts,spi)

This orbit looks like this

>>> o.plot()

We can now calculate the actions by doing

>>> from galpy.actionAngle import actionAngleStaeckel

>>> aAS= actionAngleStaeckel(pot=spi,delta=0.45,c=True)

>>> jr,lz,jz= aAS(R,vR,vT,z,vz)

These actions are also in natural units; you can obtain physical

units by multiplying with ro*vo. We can now plot these actions

>>> from galpy.util import plot as galpy_plot

>>> galpy_plot.scatterplot(lz,jr,'k.',xlabel=r'$J_\phi$',ylabel=r'$J_R$',xrange=[0.,1.3],yrange=[0.,.6])

which gives

Note the similarity between this figure and the GCS figure above. The curve shape is due to the selection (low angular momentum stars can only enter the selected radial ring if they are very elliptical and therefore have large radial action) and the density gradient in angular momentum is due to the falling surface density of the disk. We can also look at the distribution of radial and vertical actions.

>>> galpy_plot.plot(jr,jz,'k,',xlabel=r'$J_R$',ylabel=r'$J_z$',xrange=[0.,.4],yrange=[0.,0.2],onedhists=True)

With the other methods in the actionAngle module we can also calculate frequencies and angles.